-and-

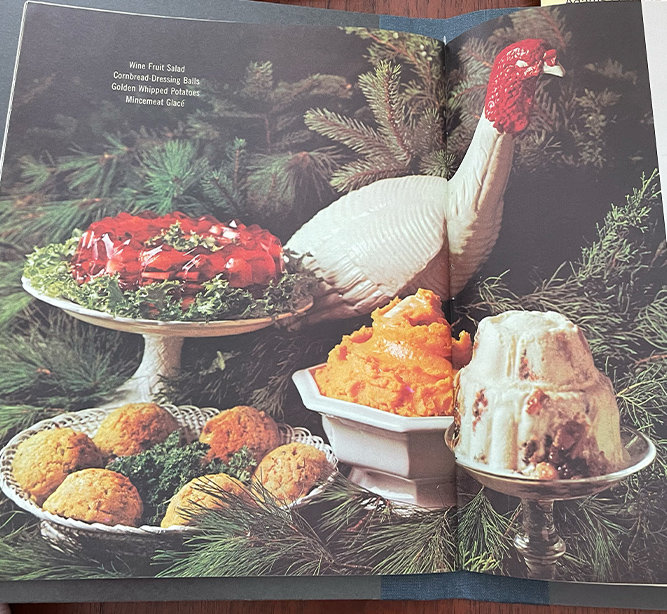

Holiday cookbooks of yesteryear offer a glimpse into how our dinner tables once looked.

Source: Library of Congress

This is a guest post by Hannah Ostroff, a public affairs specialist in the Library Collections and Services Group. It appears in slightly different form in the November-December issue of the Library of Congress Magazine.

November 22, 2024

Posted by: Neely Tucker

When you sit down for a traditional holiday meal, does your cranberry sauce resemble the fruit or retain the outlines of the can’s ridges? Does the stuffing — or is it called dressing? — go inside the turkey? Who brings the black-eyed peas? Latkes with sour cream or applesauce? Do your family traditions include tamales?

Library collections hold some 40,000 cookbooks, plus thousands of recipe booklets, archival recipes and dietary therapy books, that reflect America’s holiday food traditions — a seasonal smorgasbord of ingredients, techniques, technology and culinary viewpoints.

Cookbooks devoted to the holidays didn’t become popular until after World War II, though festive recipes nevertheless had their place. The first cookbook added to the Library’s collections was at least holiday adjacent. Thomas Jefferson’s copy of “The compleat confectioner; or, The art of candying and preserving in its utmost perfection,” a 1742 volume written by Mary Eales.

Those early cookbooks were smaller and, obviously, lacked the lush photography we associate with modern publications. They didn’t contain specific measurements or instructions, assuming readers possessed a baseline level of culinary knowledge. Imagine a recipe, like one for stewed pears by Hannah Glasse in 1774, simply telling you “when they are enough take them off.”

Cookbooks as we know them today started around the turn of the 20th century.

The books then began including elements expected by the modern home cook, at first explaining methods and measurements at the front — what constitutes a “slow cook,” for example — and later integrating that information into recipes. Instructions were geared to an audience of wives who managed their households and turned to “tried and true” authoritative recipes.

The Library has multiple editions of classics, from Bon Appetit and Betty Crocker, that were mainstays in many homes. “There’s one for every generation,” said Clinton Drake, a reference librarian in the History and Genealogy Section. “People would receive one when they got married and set up a household.”

Drake and J.J. Harbster, a culinary specialist and the head of the Science Section, have pored over stacks and stacks of holiday cookbooks.

Holiday cookbooks reflect the start of convenience foods like cake mix, which became popular in the 1940s and changed Americans’ eating habits. The way to acquire ingredients was changing too, Harbster notes — one could just pop into the store for a can of pumpkin before preparing a pie.

“Back in the day, there were no canned pumpkins, so bakers would simply cut up fresh pumpkins and stew them themselves,” Harbster said.

The detailed cookbooks that started in the late 1800s really took off along with the advent of refrigeration. The means of storing food made a big impact on how cooks planned and dined for the holidays. Virginia Pasley’s 1949 “The Christmas Cookie Book” is organized into chapters based on “cookies that keep,” “cookies that keep a little while” and “cookies that won’t keep.”

-and-

Enter the midcentury gelatin era. “The ’50s and ’60s were fabulous,” Harbster said. “They were all about salad, but these salads were not the salads we know.”

“McCall’s Book of Merry Eating,” published in 1965, offers multiple recipes for so-called salads, to be chilled in a mold and served over salad greens. One contains canned corn, a package of frozen peas and carrots and chicken bouillon.

The McCall’s cookbook also includes six (!) fruitcake recipes — plus another for fruitcake ice cream. “[T]o be mellow in time for the holidays,” the inside cover advises, “most of them should be baked shortly after Thanksgiving.” By 1982, “Betty Crocker’s Christmas Cookbook” was offering an “old-fashioned fruitcake” recipe to “evoke Christmas past.”

The rapid pace of technological development in the kitchen shaped innovations in holiday cookbooks. Cooks were eager to try out the promise of futuristic machines, like the microwave and slow cooker.

Barbara Methven describes the holiday season as the busiest time of the year in her 1980s cookbook, “Holiday Microwave Ideas.” Her book provides conventional and microwave directions. She recommends the microwave for a boneless turkey breast, not the entire bird, and while a goose is a no-go in the microwave, she has a recipe for a whole Cornish game hen heated on high for 12 to 17 minutes.

“I just love the optimism of the microwave cookbooks,” Drake said.

The Library’s collections show how regional and global representation have increased in cookbooks by major publishers. In recent decades, the industry has featured authors with diverse backgrounds sharing their own cuisines and traditions, like “Hawai’i’s Holiday Cookbook” by Muriel Miura and Betty Shimabukuro or Gwyneth Doland’s “Tantalizing Tamales.”

Kwanzaa, a holiday established in 1966, brought with it new food traditions. African American culinary historian Jessica B. Harris shares a mix of African diaspora recipes and African American cuisine in her 1995 book, “A Kwanzaa Keepsake.”

Home cooks today have greater access to ingredients than ever.

In the 1940s, Pasley wrote in her cookie book that “since the stuffs that cookies are made of come from the ends of the Seven Seas, you shouldn’t expect to be able to buy them all in one store.” She offered suggestions for where one could obtain more-challenging items. (The most unexpected ingredient in the holiday cookbook collection? The salty star of Prannie Rhatigan’s “Irish Seaweed Christmas Kitchen.”)

More contemporary cookbooks also trace a history of dietary concerns.

The Moosewood Collective, whose New York restaurant dates to the 1970s, focuses on vegetarian cooking. Its 30th-anniversary cookbook, “Moosewood Restaurant Celebrates Festive Meals for Holidays and Special Occasions,” offers menus for Diwali, Ramadan, Chinese New Year and a vegan Thanksgiving. Now, Harbster notes, “plant-based” cookbooks are widespread.

In the collection of the National Library Service for the Blind and Print Disabled, braille holiday cookbooks bring recipes to users. NLS has multiple volumes, including the braille edition of Jeff Smith’s “The Frugal Gourmet Celebrates Christmas.”

No matter the specific recipe or format, there’s often a personal tie to holiday cookbooks.

“Every holiday, it would be tradition to bring out your family’s collection of cookbooks and recipes,” Harbster said.

The holidays help keep food traditions alive, writes Joan Nathan in the 25th anniversary edition of “Joan Nathan’s Jewish Holiday Cookbook.” Nathan names recipes for their authors: “Rose family potato kugel,” “Irene Yockelson’s sweet-and-sour cabbage soup” and “my mother’s brisket.” Harris’ Kwanzaa cookbook has blank pages for family members to record their own recipes and recollections.

Making food is an expression of love — especially if you’re not a year-round cook or baker.

“This is the time when you make all of your special recipes that take a lot of effort,” Drake said. “That’s a theme runs that throughout the collection.”

What’s next in holiday cooking? Given the cyclical nature of trends, Drake predicts those molded salads are due for a comeback.

There’s no accounting for taste.