-and-

Unable to track and defeat the elusive Apache themselves, the Spanish enlisted the help of their Comanche allies — a mortal enemy of the Apaches.

Source: Library of Congress

Posted by: Mark Hartsell

Image: Courtesy

Soon after the battle, a Comanche warrior put pen to paper to tell the story, in pictures.

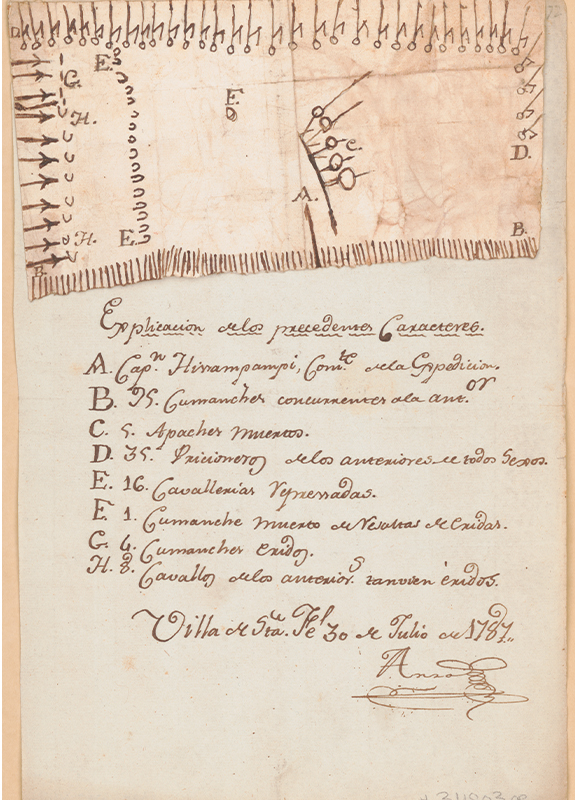

He drew a simple map, ringed with images of warriors and weapons, that chronicles a little-known, 18th-century battle between the Comanches and Apaches in the Spanish frontier province of New Mexico.

The fight, today known as the Battle of Sierra Blanca, was years in the making, and the map is now preserved in the Geography and Map Division.

Apache warriors frequently raided Spanish settlements in New Mexico, a constant concern for provincial Gov. Juan Bautista de Anza. Unable to track and defeat the elusive Apache themselves, the Spanish enlisted the help of their Comanche allies — a mortal enemy of the Apaches.

Under chief Hisampampi, the Comanches accomplished what the Spanish couldn’t. They defeated a large Apache party in far West Texas in April 1787. In July, they routed the Apaches in the Sierra Blanca Mountains of southern New Mexico — a favorite Apache staging ground for raids — and drove them in retreat down the Rio Grande Valley.

Immediately afterward, one of the Comanches drew a pictorial map that soon was passed to Anza as an official record of the battle. Officials in the capital of Santa Fe attached the map to a larger sheet and added a Spanish-language key explaining the action depicted. Anza then certified the document with a florid signature and the date of the battle: July 30, 1787.

In the map, Hisampampi (denoted by A) leads 95 warriors (B) into the fight. Five Apaches are killed (C) and 35 taken prisoner (D), and 16 horses are captured (E). One Comanche is killed (F), and four are wounded (G). Horseshoe-shaped symbols represent horses. Arrows denote warriors and horses injured in battle; Apache prisoners are shown with their heads down.

The artist drew the map on paper — an early example of ledger art, so named for the books that in later decades became a source of paper for Native American artists. Today, it’s a rare chronicle of Native history, held in the Library’s collections.