-and-

These fill volumes and folders and boxes in the Library’s Music Division, a dizzying testament to one of the great musical lives of the American 20th century.

Source: Library of Congress

Posted by: Neely Tucker

Photos: Courtesy

Ned Rorem could never stop thinking. Or writing, composing or socializing.

He kept datebooks, scrapbooks and diaries, the last of which went for thousands of pages over decades. He composed more than 500 art songs, three symphonies, four piano concertos, more than half a dozen operas and on and on. These fill volumes and folders and boxes in the Library’s Music Division, a dizzying testament to one of the great musical lives of the American 20th century.

A bon vivant in Paris and New York for more than half a century, Rorem seemed to know all the high-brow artistic set — Pablo Picasso, Balthus, James Baldwin, Jean Cocteau, Aaron Copland, Leonard Bernstein, Tennessee Williams, Noël Coward. He went on benders with Kenneth Anger, the notorious underground filmmaker. Openly gay when that was a shocking rarity, his published diaries were wildly indiscreet, creating a sensation when they were published six decades ago.

“The mediocrity of this ship’s passengers,” he tartly noted on one trans-Atlantic voyage in 1955, “is beyond belief.”

He won a Pulitzer Prize, Fulbright and Guggenheim fellowships, music commissions from famous foundations and ASCAP’s Lifetime Achievement Award and served as the president of the American Academy of Arts and Letters. Time magazine once declared him “the world’s best composer of art songs.” In 2004, the French government awarded him the Chevalier of the Order of Arts and Letters for his “significant contribution to the French cultural inheritance.” His works are still widely performed and recorded.

He was born in Indiana in 1923, got his master’s degree at The Juilliard School in New York and was soon off to Paris, the talented boy wonder. He lived there for nearly a decade.

Here he is in that city, writing in his diary on Halloween of 1956, with ominous strains of the Cold War beating down on Europe: “Winter is terribly here. And another war seems well on its way, war like a searchlight wail of mammoths straining the sky. All around in Africa and Hungary is this positive and bleeding unrest. I’m scared.”

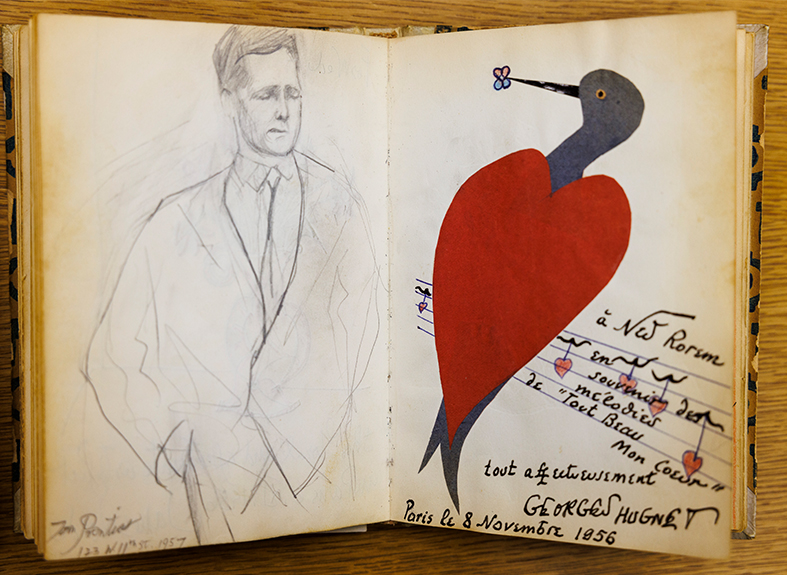

Here’s a page from one of his scrapbooks, in which he was forever getting guests to write, scrawl and sketch. It’s a casual snapshot of Baldwin, the famed novelist and activist, who scribbled on July 8, 1958: “for Ned, In the hope that we work together, soon, & long.” He signed it, “Jimmy B.”

Rorem, who died at age 99 in 2022, had been slowly donating his papers to the Library over the years. They are dazzling, in-depth and insightful. The scrapbooks are both portfolio-sized and in small notebooks, all of them filled with drawings, signatures, witty one-liners from famous friends.

Most of his entries are just a paragraph or two; a few go for several pages. They were so neatly and compulsively kept that you can open a datebook to a specific day, where you’ll see jottings of phone numbers and addresses and appointments, then open the corresponding diary to see what he penned on that day, then compare that passage to the finished manuscript page. Over and over again, his longhand diary entries are almost the same as the published piece. His diary entries are dated, but he cut the specific dates from the finished book, leaving them with more of an impressionistic, and less of a journalistic, feel.

The overall impression? Even now, one is brought up short by his mix of intimacy, intelligence and celebrity. You can imagine how this played out when his first two diaries were published in the 1960s.

“The Paris Diary of Ned Rorem,” adapted from his journals from 1951-55, wrote the New York Times in its obituary of the man, “mentioned hundreds of the famous and the obscure while serving up a pastiche of explicit reports on his sex life, pieces of music criticism and charming anecdotes.”

“Name-dropping is one thing,” the article said. “With the gossipy Mr. Rorem, it could reach the level of carpet-bombing.”

“Worldly, intelligent, and highly indiscreet,” The New Yorker opined.

He recounts spending an evening with an aging Alice B. Toklas in her famed apartment on rue Christine, more than a decade after the death of her life partner, Gertude Stein, both icons of the American expatriate community in Paris. He wrote this passage out in longhand but cut it from the published version: “And she is old, old, small and old as a unicorn or a raven flying through the sad old-fashioned smoke of other autumns, deaf, with Virgil’s style and accent, quick as a whip.”

-and-

Flipping through the pages, there are often random one-liners or phrases he seems to be trying out. “I’m in love again for the first time.” A bit of dialogue: “The phone: ‘But how will I recognize you?’ ‘I’m beautiful.’ ”

Just when you think it’s all chaff and gossip, there is a plainspoken passage from the artist alone with his work, struggling.

“What a disheartening mess it always is: the first days’ fumbling at a long work. A song or something in one sitting is almost done before begun. But the opera on Petronius that I’ve been plotting for months is now rather started so I don’t know where I am; it’s more than just music, theater. … Slowly, as days pass, if we are routine, a form appears and finally (as with wars in history) we recoil and see it all as a whole. There it is, finished; now will it work?”

Late in life, he paused to consider it all, this relentless minute cataloguing, this constant self-examination. In “Lies: A Diary, 1986-1999,” he wrote on Jan. 15, 1996: “Why keep a journal? To stop time. To make a point about the pointlessness of it all. To have company. To be remembered. For there is much to be recalled, with no one to do the recalling.”