-and-

In the final year of the 19th century, a little-known pianist and composer named Scott Joplin and a Missouri music publisher named John Stark sent a small package to the U.S. Copyright Office at the Library.

Source: Library of Congress

November 21, 2024

Posted by: Neely Tucker

In the final year of the 19th century, a little-known pianist and composer named Scott Joplin and a Missouri music publisher named John Stark sent a small package to the U.S. Copyright Office at the Library.

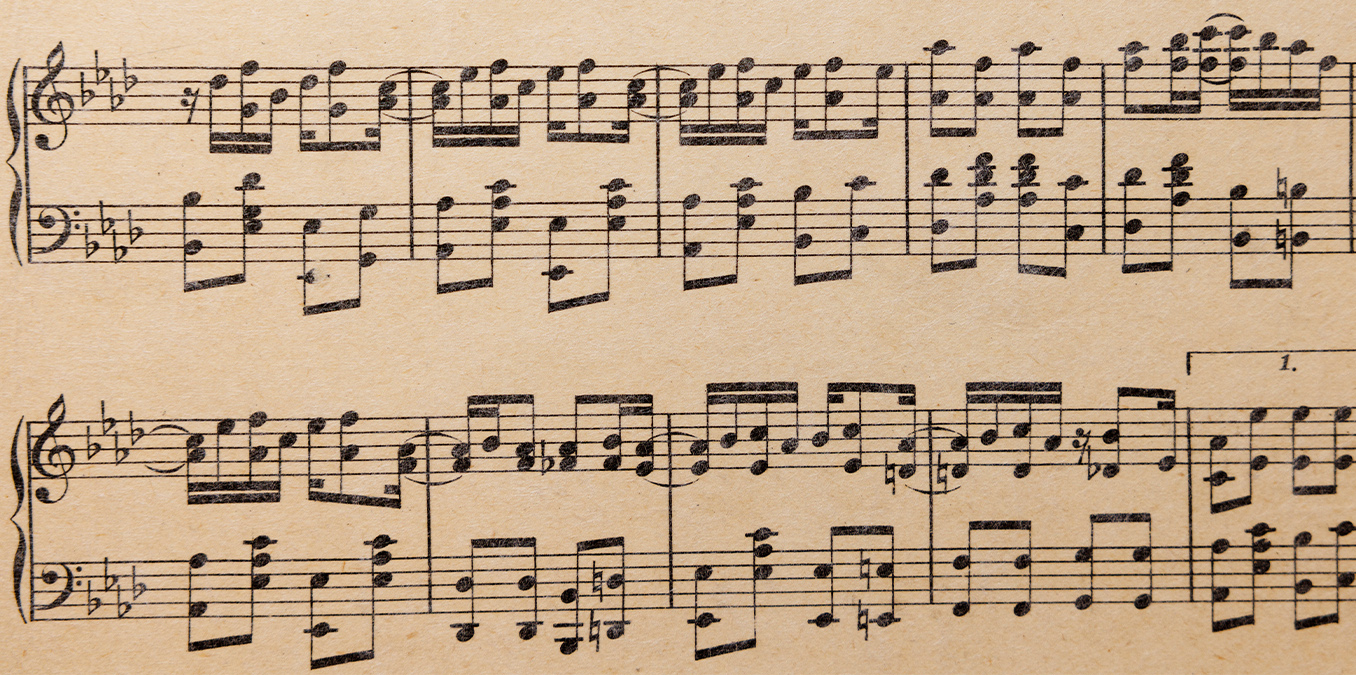

Tucked inside were two copies of sheet music for a highly syncopated, upbeat piano piece with intense flurries of notes — more than 2,000 in a song that took less than three minutes to perform. It was called “Maple Leaf Rag.”

It blew the doors off everything.

“Maple” sold 75,000 copies of sheet music in six months, went on to sell millions both as sheet music and in dozens of recordings. It changed the lives of both men and of American popular music. It became the signature piece of ragtime, which also itself lent its name to an era of American life and helped set the foundations for jazz.

“It was a wild success story of fairy-tale proportions,” wrote historian Edward A. Berlin in his definitive “King of Ragtime: Scott Joplin and His Era.”

Joplin, who was born 156 years ago this week in northeast Texas (Nov. 24 to be exact), wrote dozens of ragtime pieces, a ballet and two operas and eventually became regarded as one of the nation’s most significant composers and cultural icons.

Decades after his death, he was awarded a Pulitzer Prize for “his contributions to American music” and honored with a U.S. postage stamp. The Library’s National Recording Registry included his work in its inaugural class of 2002 — a group that also included the first recording of George Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue,” Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech and Thomas Edison’s landmark 1888 recordings. A St. Louis rowhouse Joplin rented for a year or two after 1900 (the only residence of his known to still exist) was named a National Historic Landmark and is maintained as a Missouri Historic Site.

But when Joplin died in 1917 in New York — of syphilis, at 48, after nearly a decade of illness — he was destitute and largely forgotten. There were only a few photographs of him known to survive. There were no recordings of his voice or of him playing the piano. The only echo of him at the keyboard are heavily edited player piano rolls, the ones preserved in the NRR, and even those were made late in life when his skills were vastly diminished.

“We have very few actual documents or artifacts directly associated with Scott Joplin,” wrote Larry Melton, founder of the Scott Joplin International Ragtime Festival in Sedalia, Missouri, in a Library article for Joplin’s induction into the NRR. “Only a few signatures and annotations bear his handwriting.”

Like the legendary New Orleans jazz trumpet player Buddy Bolden, who also died without a recording, Joplin seemed to fall into the long shadows of American history, a figure composed of equal parts man and myth.

So it’s quite the feeling today to walk into the Music Division and see, resting gently on a table, the two copies of “Maple” that Joplin and Stark had printed and mailed to the Library in 1899.

Now 125 years old, they’re a bit faded, sepia-toned and with the edges a little ragged. The cover features crudely drawn images of two well-dressed black couples out for a night on the town — common to the era, but seen as cartoonish and racist today — taken from a tobacco advertisement. Still, it credits Joplin as composer just below the title and blares his name out in bold type. It sold for 50 cents. Joplin got a penny from every sale. It made him moderately well off for several years. It’s possible the tune was named for the Maple Leaf Club in Sedalia, a black dance hall where he frequently played, but no one is certain.

“No original manuscript for the ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ is known to survive,” says Raymond White, a senior music specialist in the Music Division, “so these two 19th-century copyright deposits of this iconic music are about as close as we can get to Joplin himself.”

When you gently open the cover sheet — a sensation something like stepping back into the ragtime era — you see the cascade of musical notes running up and down and spilling over the staffs, showcasing the complicated, joyful, bouncing piece that so delighted audiences. The prevailing popular music of the time tended to be mawkish and sentimental; this had to land like a lightning bolt. It is so difficult to play that Joplin himself took time to rehearse before playing it in public, and later in life, as his illness took hold, he could scarcely play it at all.

Legendary stride pianist Eubie Blake, a generation younger than Joplin, remembered seeing him perform in Washington, D.C., around 1908 or so.

-and-

“He played at a party on Pennsylvania Avenue but he was very ill at the time,” Blake remembered in “Scott Joplin and the Ragtime Era,” by Peter Gammond, the famed British music critic. “He played ‘Maple Leaf Rag’ but a child of five could have played it better. He was dead but he was breathing. I went to see him after but he could hardly speak he was so ill.”

Though much of Joplin’s life is lost to the era and the ambiguities of personal memories, the Library documents much of ragtime’s history and some of his. There are other early copies of “Maple” and his other sheet music; a 1907 copy of The American Musician and Art Journal that has one of only known photos of Joplin (seen at the top of this article); and the oldest known recording of “Maple,” in 1906 by the Marine Corps Band. There also are also interviews with ragtime musicians Max Morath and Joshua Rifkin and then another with Patricia Lamb Conn, whose father, composer Joseph Lamb, knew Joplin well.

The Library also has the adaptations from Joplin’s work that Marvin Hamlisch turned into the Oscar-winning score for the hit 1973 film “The Sting.” (There is also the Oscar statuette itself.) The soundtrack, composed almost entirely of Joplin tunes, topped the Billboard Hot 100 for five straight weeks in 1974, launching him back into pop culture 57 years after his death. That popularity led to the resurgence and recognition of his career.

Joplin’s prime years were in Missouri and the last decade of his life in New York City, but his music has seemed to capture something timeless in the American imagination.