-and-

Edgar Allan Poe died 175 years ago today, Oct. 7, 1849, in a Baltimore hospital under circumstances that no one has ever fully understood.

Source: Library of Congress

October 7, 2024

Posted by: Neely Tucker

He was en route from speaking engagements in Virginia to New York when he went missing in Baltimore. After several days, he was found the night of Oct. 3, the day of a local election, lying outside a pub that doubled as a voting precinct. He could barely speak, apparently had been beaten and was wearing shabby clothes that were not his. There have been endless theories about he came to be found in this state, from rabies to a brain tumor to severe alcoholism. Many historians say it’s most likely that he was the victim of cooping, a brutal form of voting fraud in which victims were violently forced to impersonate legitimate voters at the polls, oftentimes with liberal amounts of alcohol involved.

In any event, Poe lingered for four days in a windowless hospital room, never regaining coherence. He died at 5 a.m. on Oct. 7. He was 40.

Among his literary masterpieces was “The Raven,” which began with one of the most famous lines in American poetry: “Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary…”

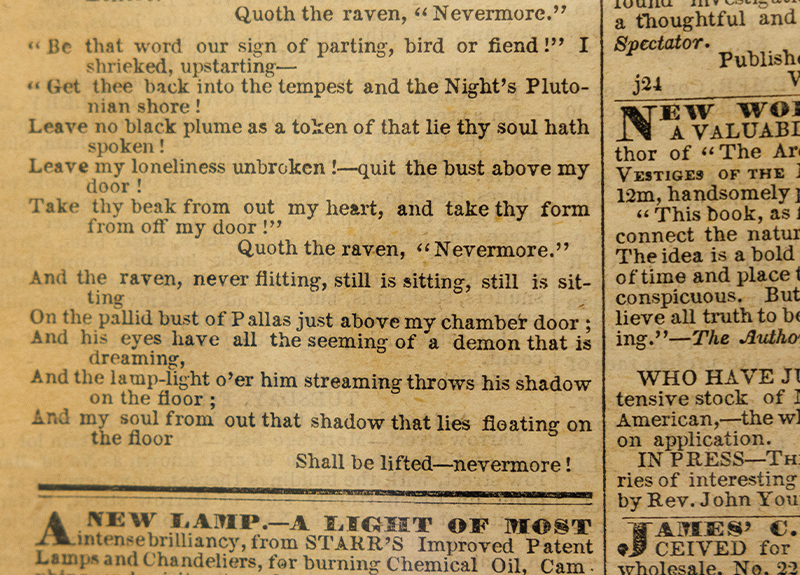

Though Poe and the poem are now closely linked with his sometimes home and burial place of Baltimore (the titular bird is now the mascot for the city’s NFL franchise), he was born in Boston and educated as a youth in England and the poem was written in New York. It first appeared in the New York Evening Mirror on Jan. 29, 1845. It was buried on an inside page amid ads for lamps and sheet music.

Poe spent a lot of time thinking about burying things (like tell-tale hearts), but this particular newspaper copy was headed for immortality.

“The Raven,” the dark tale of a grieving young lover encountering a black bird with a fiery stare and a one-word vocabulary, is one of the most anthologized and instantly recognizable poems in American history.

The Library’s Rare Book and Special Collections Division preserves an original copy of the Evening Mirror that day, marking the moment the poem entered the national culture.

It was clearly inspired by Poe’s tragic circumstances.

Poe and his first cousin, Virginia Eliza Clemm Poe, had married in 1836, when she was 13 and he was 27. There has been much speculation about their relationship (even for the era, she was extremely young to be married) but the pair seemed devoted. Her adoring letters refer to him as Eddie.

The couple was struggling to get by on the earnings from Poe’s literary career when, in 1842, Virginia contracted tuberculosis. She was just 18. It was a slow and terrible way to die — as the bacterial infection spread in the lungs, it caused bloody coughs, chills, fever, weight loss and night sweats. As the years ground on, the disease waxed and waned. Poe, already possessed of a macabre imagination and often debilitated by alcohol, later described the period this way: “I became insane, with long intervals of horrible sanity.”

It was during this terrible period that he wrote “The Raven.” He seemed to be anticipating, with great dread, the depression that would crush him after Virginia’s death:

“Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the bleak December;

And each separate dying ember wrought its ghost upon the floor.

Eagerly I wished the morrow;—vainly I had sought to borrow

From my books surcease of sorrow—sorrow for the lost Lenore—

For the rare and radiant maiden whom the angels name Lenore—

Nameless here for evermore.”

He published it in January 1845, with the bird’s resounding refrain of “Nevermore” becoming a sensation. The editors at the Evening Mirror considered its remarkable gothic nature, haunting phrases, perfect meter and recognized genius: “It will stick to the memory of everybody who reads it,” the paper wrote.

-and-

In an essay published the next year, “The Philosophy of Composition,” Poe uses the poem as an example of his work method. He never mentions Virginia’s impending death as an influence, but late in the essay he does explain the poem’s dark power.

The first part of the poem is straightforward, he wrote. The beautiful Lenore has died. Her grieving suitor is reading late one night, trying to fend off his grief. A raven raps at the window and flies in when it is opened. The narrator, more bemused than alarmed, reasons that the bird has escaped its owner, happened by his illuminated window late at night and sought refuge. It can mimic speech, like a parrot, but knows only one word: “nevermore.”

A little weird, sure, but this is all rational.

But then the narrator reclines on a sofa where Lenore had often lain, resting his head “on the cushion’s velvet lining.” Meant to be a comfort, the soft fabric instead reminds him that Lenore’s cheek had often lain on this exact spot. The shock sends his mind into hallucinations:

“Then, methought, the air grew denser, perfumed from an unseen censer

Swung by Seraphim whose footfalls tinkled on the tufted floor.”

The world has warped — seraphim are celestial creatures, winged angels — and our narrator now believes that he is hearing the footsteps of invisible spirits on the carpet all around him.

Now things turn brutal. The narrator knows perfectly well that the bird can only say “Nevermore,” but he begins to ask it hopeful questions — Is there spiritual help for his pain? Will he and Lenore be reunited in the afterlife?

“Nevermore,” thunders the bird, lashing him with the pain he wanted. This is a sort of perverse masochism, Poe writes in the essay, as the narrator is impelled by “the human thirst for self torture.” The more pain, the more he likes it: “…he experiences a frenzied pleasure in so modeling his questions as to receive from the expected ‘Nevermore’ the most delicious because the most intolerable of sorrow.”

Then, just when we think it’s all over, Poe drives in the dagger.

In the last stanza, he changes the tense from past to present, from a night in the past (“.. it was a night in bleak December”) to the horrifying present. The narrator hasn’t been remembering a quaint evening of yore, but is reporting from right now and … the raven is still there. We have no idea of how much time has passed, but we get the idea it is considerable because the narrator says “still” twice. There are no more whiffs of invisible angels, only the glare of a demon’s eye:

“And the Raven, never flitting, still is sitting, still is sitting

On the pallid bust of Pallas just above my chamber door;

And his eyes have all the seeming of a demon’s that is dreaming,”

The bird, we know now, will never leave. There is no balm in Gilead. There is no escape from grief. The last use of the word “Nevermore,” Poe wrote, “should involve the utmost conceivable amount of sorrow and despair.”

Virigina died two years and one day after “The Raven” was published. While her corpse lay on the deathbed, Poe had an artist paint her portrait. It is the only image of her known to still exist.

-and-

In life, as in “The Raven,” Poe never seemed to fully escape his grief. He was sometimes found after dark in the years to come, sitting beside her grave. His last completed poem was “Annabel Lee,” in which the unnamed narrator is haunted, much like the protagonist of “The Raven,” by the death of his beautiful young love. At the poem’s conclusion, the narrator pictures climbing into the tomb with her corpse:

“And so, all the night-tide, I lie down by the side

Of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride,

In her sepulchre there by the sea,

In her tomb by the sounding sea.”

Autumn is Poe’s season, the time of year when his dark, dazzling works seem to most come to life. Halloween still seems like a holiday he would have created if hadn’t already existed; the long night, the ghosts, the fears of The Thing in the Dark. And finally, there is the everlasting sense of horror from the last lines of “The Raven” — there will never be any solace from the grave; only the dark, deep, terrible silence.