-and-

Like the endless reinventions of Western classics, from “The Iliad” to “Romeo and Juliet,” “Genji” holds a central place in Japanese culture, with new works adding to that heft as time goes by.

Source: Library of Congress

Images: Courtesy

“The Tale of Genji,” one of the foundational works of Japanese literature, was written 1,000 years ago and is more than 1,000 pages long. Penned over the course of a decade or so by Murasaki Shikibu, it is widely considered the world’s first novel. It’s also a landmark of women’s world literature.

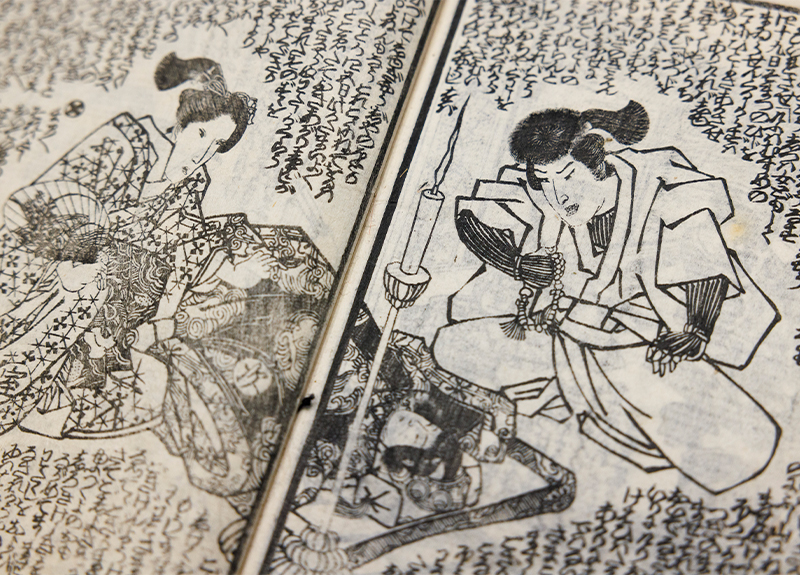

The Library has many iterations of “Genji” from down the centuries — full copies, in Japanese and in translations, plus summaries, satires and what you might call graphic novel versions from 17th century. Like the endless reinventions of Western classics, from “The Iliad” to “Romeo and Juliet,” “Genji” holds a central place in Japanese culture, with new works adding to that heft as time goes by.

The Library recently added to its impressive “Genji” collections with a beautiful edition of Genji kokagami, or “A Little Mirror of the Tale of Genji,” set in wooden moveable type, from around 1625. It’s a summary of the original with excerpts and explanations, filling three slender notebook-size volumes with thin pages and delicate type. The typeface is so finely wrought that it appears at first glance to be calligraphy.

This truncated edition was extremely popular in its day, as it was important in Japanese society to be on a conversational basis about “the shining prince,” as the titular Genji was known, even if reading the entire opus was not pragmatic. Call it the shorthand for the smart set.

“It made the book much more accessible to many more people,” said Jesse Drian, Japanese reference librarian in the Asian Division, where the books are held.

But “Genji” is challenging on several levels — its length, archaic language, confusing naming conventions (almost everyone is referred to by their titles, not their actual names), huge cast and a very slow pace that follows characters for decades. Genji dies two-thirds of the way through … and there’s still more than 300 pages to go.

Given all this, it wasn’t translated into English until the late 19th century. When Virginia Woolf read Arthur Waley’s landmark 1925 translation, she was mesmerized.

“All comparisons between Murasaki and the great Western writers serve but to bring out her perfection and their force,” she wrote in a review for Vogue magazine. “… But it is a beautiful world; the quiet lady with all her breeding, her insight and her fun, is a perfect artist … life expressed itself chiefly in the intricacies of behaviour, in what men said and what women did not quite say.”

The scholar Royall Tyler published a highly regarded translation into English in 2001, replete with explanations, footnotes, character lists and helpful drawings and illustrations. He was exhausted by the effort.

“After eight and a half years spent translating, pondering, and discussing it, I still cannot imagine how she created it,” he wrote in Harvard Magazine that same year.

So what’s all the fuss?

Like most ancient epics, it’s complicated.

“Genji” is a poetic, delicately wrought story about the life and loves of the dashing, sophisticated Genji in Heian period Japan, around 1000. He’s courtly, refined, educated, generous and handsome, but denied a shot at the throne by his father.

But rather than a tale from a long-ago oral tradition finally set down into print, or the rousing tale of a swashbuckling prince out to claim the throne denied him, it’s an intricate examination of aristocratic manners and romantic relationships in the royal city, with a keenly sensitive eye turned toward nature. It’s often said that the book is more a series of independent stories set around a central character rather than a single narrative.

Shikibu was a lady in waiting amid the aristocracy at court and spent more than a decade writing “Genji,” perhaps composing the elegant chapters one at a time for her patron and others. (Woolf admired a passage in which flowers unfolded themselves “like the lips of people smiling at their own thoughts.”) The most refined art at the time was poetry, and in the book she wrote some 800 short poems in Genji’s voice, exquisitely wrought verses that illustrate the book’s sophistication.

The author knew this world well. The capital at the time was modern-day Kyoto, and Shikibu’s father was a poet and aristocrat in the lower branches of government. It’s fitting that Murasaki Shikibu is a nickname of sorts, following the mores of the period in which women were often referred to by references to their male relatives.

“Shikibu” translates as “Bureau of the Ceremonial,” a position her father had held, and “Murasaki” is a plant that produces lavender dye used in clothing. It is also the name of the book’s heroine. (No one is certain of the author’s actual name, although many of her life details are known.) She kept to that practice in the book. As Tyler notes in the introduction to his translation, women without a title “may have no personal appellation at all in the narration.”

Also, verbs don’t always have a clear object. Even after hundreds of years of scholarship, Tyler notes, “it is still possible to argue that this or that speech or action should be attributed to someone else.”

As you might expect, this gets confusing over the course of 1,000 pages covering decades of time and a cast of a couple hundred characters.

Finally, it was composed in a formal version of the language that passed from common use, making it difficult even for Japanese readers to comprehend. (Think of trying to read a work written in Middle English.)

So began the centuries of summaries, the quotations, the heavily illustrated satires — all from one book bringing a country, and then the world, a little bit closer together. Things are different now, but people? As Shikibu shows us, not so much.