-and-

This vision lives only in the imagination, a story of architectural designs that went unrealized.

Source: Library of Congress

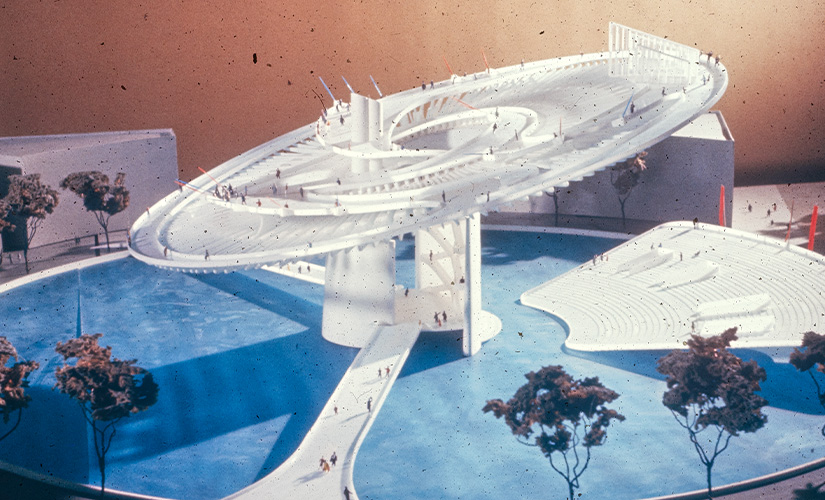

Post by Sahar Kazmi, a writer-editor in the Office of the Chief Information Officer. It also appears in the September-October issue of the Library of Congress Magazine. (Featured Photo: Paul Rudolph’s proposed “Galaxon” for the 1964 World’s Fair was never built. Prints and Photographs Division.)

Imagine this: It’s a crisp fall afternoon in the nation’s capital. You stand beside the colonnades at the base of the Washington Monument and look up at an elaborate statue of the first president among his rearing horses. Next, you take in the vaulted ceilings and intricate arches of the Gothic palace of the Library of Congress. In the evening, you grab a bite along the Washington Channel Bridge, a modern rendering of Florence’s Ponte Vecchio.

Perhaps in another life. This vision lives only in the imagination, a story of architectural designs that went unrealized. A Washington, a world, that might look quite different were it not for economic pressures, political will or pure chance. For as many grand and iconic structures as we now know by heart, there are tenfold more that were never built at all.

The Library’s Prints and Photographs Division hold a fascinating array of architectural drawings going back as far as the 1600s. They offer a look into what could have been had the stars aligned.

The well-known obelisk of architect Robert Mills’ Washington Monument was originally envisioned on a raised colonnade, punctuated by great statues. John L. Smithmeyer and Paul J. Pelz’s Italian Renaissance vision of the Library of Congress beat out a dramatic Gothic castle from Alexander Esty in a pair of congressionally authorized design competitions.

Much later, in the 1960s, architect C.W. Smith imagined D.C. in the Florentine style, drawing a contemporary version of the Italian city’s famed Ponte Vecchio bridge. Her idea, designed as an open-air pedestrian hangout complete with cafe tables and striped awnings, was never commissioned by the city.

Paul Rudolph, whose modernist, geometric designs can be found across America today, had a few misses too. A sprawling attempt at combining residential features with traffic flow in a growing New York City, Rudolph’s Lower Manhattan Expressway, or LOMEX, drew political debate for years before it was eventually scrapped.

His concept for the 1964 New York World’s Fair also was ambitious. Dubbed the spacey-sounding “Galaxon,” Rudolph’s architectural drawing is about 19 feet long, featuring a dramatic concrete walkway leading to an enormous, tilted flying saucer-shaped viewing structure. It was rejected in favor of Gilmore D. Clarke’s more earthly “Unisphere” steel globe.

-and-

Space age urban utopianism was a common theme in midcentury design aesthetics. Architect and industrial designer Wilbur Henry Adams, who became better known for his work on the Oliver tractor, once was an inventive student at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. While there, he mocked up the “Study Playroof,” an ultramodern urban playground in the middle of Manhattan. Here, children ride on seesaws and bicycles beside the wing of an expansive helicopter landing deck. Just another day in New York City!

Perhaps the most perfect example of this style is a creation from none other than Frank Lloyd Wright. In the last project he worked on before his death, Wright collaborated with architect William Wesley Peters on a futuristic wonderland for Ellis Island. Called the “Key Project,” their colorful rendering seems a far cry from Wright’s quintessential prairie style. In it, a series of huge domes surround a circular housing podium intersected by triangular sundecks and winding towers. It’s Trek-y, a little Seussian, and positively sci-fi.

Architecture is often a catalog of the unmade. Lucky, then, that even our imagined futures are saved alongside our histories at the Library.