-and-

“A Soldier’s Journey,” a new bronze statue, was recently unveiled at the World War I Memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Pershing Park, set at the foot of Capitol Hill.

Source: Library of Congress

November 7, 2024

Posted by: Neely Tucker

This is a guest post by Cheryl Fox, an archives and history specialist in the Manuscript Division.

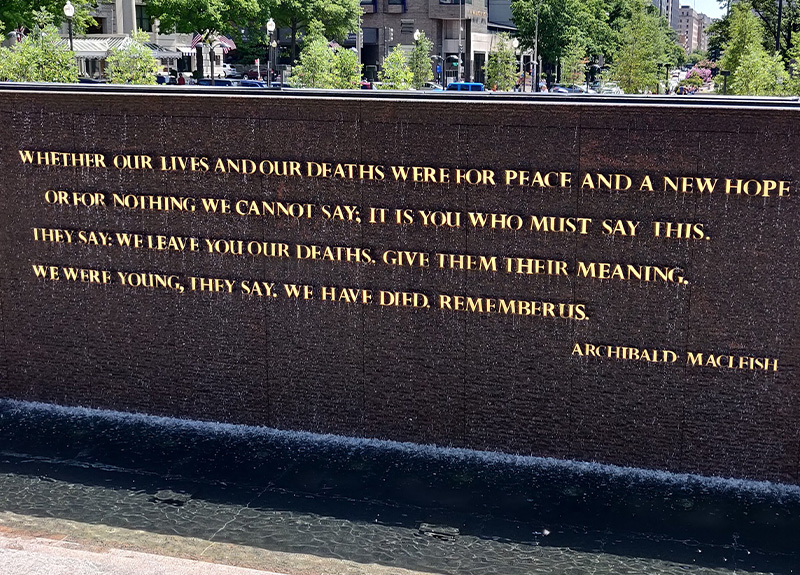

An excerpt from “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak,” a poem by former Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, adorns another wall at the park. Both mark a fitting tribute to the nation’s fallen soldiers this Memorial Day.

In September, the National Park Service unveiled the final element of a new national World War I memorial in Washington, D.C.’s Pershing Park. Titled “A Soldier’s Journey,” the bronze sculpture by Sabin Howard depicts the experience of a single soldier, from enlistment to homecoming, through 38 human figures.

Carved on its opposite side is an excerpt from a poem by former Librarian of Congress Archibald MacLeish, “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak,” which concludes with these famous lines, set in all capital letters:

“WHETHER OUR LIVES AND OUR DEATHS WERE FOR PEACE AND A NEW HOPE

OR FOR NOTHING WE CANNOT SAY; IT IS YOU WHO MUST SAY THIS.

THEY SAY: WE LEAVE YOU OUR DEATHS. GIVE THEM THEIR MEANING.

WE WERE YOUNG, THEY SAY. WE HAVE DIED. REMEMBER US.”

MacLeish wrote the poem in 1943 during his tenure as Librarian. Its universal message, calling on citizens to remember and honor fallen soldiers, resonates with MacLeish’s experiences during World Wars I and II.

He interrupted his undergraduate studies at Yale University in 1917 to join the Yale Unit, or Mobile Hospital No. 39, as an ambulance driver. He later joined the U.S. military and commanded an artillery battery at the second Battle of the Marne in France.

By the late 1930s, MacLeish was a well-known cultural figure and multiple prize-winning author closely allied with New Deal initiatives. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt appointed him Librarian in 1939.

Throughout his five-year tenure, MacLeish worked with the Roosevelt administration as a speech writer and spokesman. When asked to contribute to the 1943 War Bond campaign, MacLeish wrote “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak.”

It was published in newspapers on Sept. 16, 1943, and appeared in the October 1943 issue of the Library of Congress Information Bulletin. An accompanying note reported that MacLeish read it at a general meeting of Library employees on Sept. 10.

After the second World War, Librarian of Congress Luther Evans, who succeeded MacLeish in 1945, asked Congress to provide funds to commemorate Library staff members who died during the war. A white marble plaque with the names of those lost etched in gold resulted. It was dedicated on Dec. 7, 1948, and sits just outside the Librarian’s ceremonial office in the Jefferson Building. A commemorative booklet produced for the dedication included photos and details about fallen staff members — and “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak.”

MacLeish was one of the nation’s most honored and respected poets and intellectuals in the first half of the 20th century. He was awarded three Pulitzer Prizes and an Academy Award, among other high profile honors.

The Library preserves his papers. Many of the public statements, publications and speeches he made during his time as the Librarian appear in the online presentation Freedom’s Fortress: Library of Congress, 1939–1953. The collection includes documents, photographs and printed material from the LC Archives collection and the papers of MacLeish, Supreme Court Justice Felix Frankfurter and Manuscript Division chief David C. Mearns.

You can listen to MacLeish reading some of his poems at the Library’s Coolidge Auditorium in 1963 and in 1976 (though “Soldiers” is not included.)

MacLeish is credited with greatly reorganizing the Library and helping turn it into the national institution it is today. In 1942, during World War II, he described its role in sweeping terms: “World events have made the Library of Congress more important now than it has ever been. Today it is, physiologically speaking, the nerve center of our national life.”